Past Life Influences

by Gina Cerminara

by Gina Cerminara

The solving of riddles is an instructive pastime. Underlying the solution of many a child’s trick is a significant principle of logic or of thought. Perhaps, then, when we come to that most important of all riddles—the riddle of man’s identity, his origin—we can apply to it the wisdom learned from a simple match trick.

In this trick a person is given six matches and asked to form with them the outline of four equilateral triangles. He begins confidently to make triangular arrangements, but his confidence soon wanes. Indeed, he finally despairs of finding the solution. The problem cannot be solved until it occurs to him to manipulate the matches in three dimensions rather than two, and to make an upright pyramid rather than a fruitless combination of flat triangles.

The enigma of man is, in a sense, comparable to the problem of the matches. Only through an added dimension—in this case, the dimension of time—does it seem likely that man will be able to understand himself.

The birth and death of man’s body are commonly considered to be the beginning and ending of man. But if it could be demonstrated scientifically that man is not merely a body, but also a soul inhabiting a body; and that, further, this soul existed before birth and will continue to exist after death, the discovery would transform psychological science. It would be as if a shaft had been dropped from surface levels of soil to deep-lying strata of the earth; modern “depth” psychology would appear as superficial as a two-inch hole for the planting of an onion by comparison with a two-mole shaft for the extraction of oil.

First of all, such an added dimension of time would enlarge man’s understanding of personality traits. Psychologists have for some time been making close statistical and clinical studies of the qualities that compose personality. These studies are monuments to the ingenuity of man’s mind; they have had many practical applications in personnel work, vocational guidance, and clinical psychology—and yet they represent what would seem to be only the narrow foreground of man.

Acceptance of the reincarnation principle throws a floodlight of illumination on the unnoticed background. The landscape so illumined has a strange and beautiful fascination of its own, but its principal importance is that within it can be discerned the slow, winding paths by which traits and capacities and attitudes of the present were achieved. Or, to change the analogy, it is as if reincarnation revealed the submerged eight-ninths of an iceberg, of which psychologists had been painstakingly examining the visible ninth.

The Cayce files provide numerous examples of this added dimension—time—and of the manner in which it explains the present personality. In one reading Cayce told of a soldier of Gaul who was taken prisoner by Hannibal and forced to row in the galleys of the trade ships. He was cruelly treated by his colored overseers, one of whom finally beat him to death. This took place three lifetimes ago, but a hatred against the colored race engendered by that intensely painful experience persisted, deep in the unconscious, over almost twenty-two centuries of time. In his most recent incarnation, the entity was an Alabama farmer. Throughout his long life he hated Negroes with a fierce and unrelenting venom; at one time, indeed, he founded a Society for the Supremacy of the White Race.

This is a typical example of an attitudinal carryover from one life to the next. There are dozens of similar ones in the life-reading files. A certain newspaper columnist has for many years nourished an intense anti-Semitic attitude. This is seen by her life reading to stem from an experience in Palestine when she was one of the Samaritans who came into frequent and violent conflict with their Jewish neighbors.

A thirty-eight year old unmarried woman had had several romances in her lifetime, but she was never able to commit herself to marriage because of a deep-seated distrust of men. This wariness sprang from an earlier experience when her husband deserted her to go on the Crusades.

A woman whose tolerance of religious beliefs was outstanding was told that she had gained that quality while a Crusader among Mohammedans. Meeting these people of an alien faith she realized for the first time that idealism, courage, kindness, and mercy exist even among non-Christians; and the impression was so strong as to leave her with a lasting sense of religious tolerance.

On the other hand, an advertising writer of notable skepticism in religious matters had also been a Crusader, and had been so profoundly disgusted by the disparity between religious profession and practice among the people with whom he associated as to acquire a deep-seated distrust of all external professions of faith.

Here, then, we see three types of attitudes—toward race, toward the opposite sex, and toward religion—the basis for which was presumably laid in a previous incarnation. Naturally there had to be in each case certain contemporary environmental circumstances to evoke such a response. The man who hated Negroes was born in the South in 1853, and the customs and traditions of his environment provided a favorable culture for the germ of race-dominance sentiment. Similar possibilities of contemporary influence can be argued in the other cases cited, or in any of the numerous similar instances in the Cayce files, but the intensity of many such attitudes, and the fact that other persons exposed to the same environmental influences do not react in the same manner, would seem to favor a more deeply founded cause than that observable in present-life circumstances.

Psychiatrists concur in the view that the major life attitudes of the psyche arise from the unconscious. The reincarnation principle merely expands the scope of the unconscious to include the dynamics of past-life experience. As in the case of physical disease, there is added a longer range of time within which the point of origin may be found.

Like attitudes, the likes, dislikes, and interests of people are an important component of human personality. The basic instincts of self-preservation, reproduction, and mastery are intimately involved in all the more superficial interests of our life. However, over and beyond the basic needs common to all humanity, there is wide diversity in the way these primary urges express themselves as interests and enthusiasms in different people.

In the same family of five children, for example, one child may take an eager interest in butterflies, another in music, a third in mechanics, a fourth in painting, and a fifth in mischief. For this diversity of talent and outlook the usual psychological explanation is that each individual’s makeup is primarily determined by the hereditary endowment of his genes, and secondarily by psychoanalytic factors of position and experience in the family constellation. This explanation is thoroughly reasonable as far as it goes; but to one whose horizon of inquiry includes even the possibility of reincarnation it is inadequate. The Cayce readings place talent and interest firmly in the heredity of the soul itself rather than in the heredity of one’s grandparents. In our hypothetical family of five, there must have been, by the Cayce view, circumstances in previous lives which laid the basis for the present bent.

The Cayce files contain the following instances of past-life origin or interests. A certain New York dentist was born and brought up in the metropolis where he now successfully practices his profession. His family for many generations were city-bred people. Though happy in his profession and an enthusiast of city life, he periodically feels an urge to go out into the fields and streams with his gun and fishing rod and camp in the wilderness alone. This intense interest in nature and outdoor life, while not unusual, is an inconsistent element in his thoroughly urban character, but by the reincarnation principle it becomes understandable. According to his Cayce reading he was, in his former life, a Dane who came to this country at the time of the early Dutch settlements. He lived in New Jersey, in a region of many marshes, lakes, and streams, and became a trapper and dealer in furs. The hunger for woods and streams remains with him, though it must now be subordinated to the principal life task of the present incarnation.

Many persons feel an intense attraction for a specific geographic locality. Such an attraction is frequently attributed by the readings to a happy previous sojourn there. A certain East coast business woman, for example, longed for many years to go to the southwestern part of the United States. She finally was able to make the change, and now lives in New Mexico, where she works as a hotel executive. According to her reading she had had two previous experiences in this portion of the country, and her love for the regions had persisted through the intervening centuries.

Four persons who had, respectively, a pronounced love of the South Sea Islands, New Orleans, India, and China, were told that they had had experiences in these places before and for this reason felt a strong affinity for them.

Interest in certain types of artistic or professional activity is similarly traced by the readings to past experience. One woman’s absorbing interest in the Greek dance and drama arose from an experience in Greece when these art forms were at their height. A boy’s marked interest in telepathy had its basis in an incarnation in Atlantis as a teacher of psychology and thought-transmission; a beautiful girl’s almost fanatic interest in aviation also stemmed from an Atlantean experience as a pilot and director of communications. A woman’s interest in helping crippled children had its origin in a Palestine experience, when, under the influence of the teachings of Jesus, she began to succor the crippled and sick. A research engineer, for many years active in the Technocracy movement, was once an Atlantean active in the scientific administration of the country.

This interest carryover from the past would seem to display itself with particular distinctness in the life history of notable people. We are speaking here not on the basis of a Cayce reading taken on such people, but on the basis of known biographical facts interpreted in the light of the Cayce data.

Consider, for example, the case of Heinrich Schliemann, the German archaeologist who discovered the remains of the buried city of Troy and thus established the historical basis for the great Homeric epic. He was the son of a poor pastor of a North German village, yet since early childhood had been fascinated by the story of the Iliad, and conceived the ambition of learning Greek and finding the original site of the Trojan story.

During the first thirty-five years of his life Schliemann amassed the fortune which enabled him later to achieve his archaeological purpose. He became an extraordinary linguist, but was especially an enthusiast about Greek and all things Hellenic. In later years he used Homeric forms of address in conversation, and his biographer relates that he held a copy of Homer over the head of his son and recited Homeric verses to him before he handed him over to the Greek priest to be baptized. This is only one of his hundreds of similar enthusiastic extravagances. So inordinate an ardor becomes understandable if one sees it as a form of homesickness of the soul which remembers an era when it was happy and attempts to reestablish itself in the same milieu.

Numberless other examples of the same sort suggest themselves from the annals of biography. Another striking instance is the case of the writer, Lafcadio Hearn. Born on an Ionian island, son of an Irish father and a Greek mother, Hearn wandered from Greece to England to America to the French West Indies and finally found his “true spiritual home” in Japan, where he married a Japanese woman, assumed a Japanese name, and became a teacher in a Japanese school. His amazing intuitive grasp of the Japanese point of view, his extraordinary ability to interpret the Japanese to the Occidentals and the Occidentals to the Japanese appear less extraordinary if one sees them as the outgrowth of a possible former Japanese incarnation, that he was impelled irresistibly to recreate.

T. E. Lawrence is another example of a man who “had it in his blood,” as one biographer puts it, to deal with masterly skill with the Arabs and, indeed, to become one of them. He was never “at home” in his English fatherland or with his English family. School bored him except for the Crusades and the study of medieval castles and fortifications. His phenomenal success as a military leader of the Arabs can perhaps be understood as the completion of some previous adventure in the Middle Ages, when he himself was an Arab and a military strategist, and died before fulfilling what he conceived unconsciously to be his incarnation’s purpose.

Exotic interests like these are found not only among the great and near-great; they are found also among the people who form one’s circle of acquaintance.

Traits, like interests and attitudes, are important elements in the analysis of personality, and the Cayce files yield some fascinating examples of their past life origin. The wife of a certain Middle West millionaire was extremely dictatorial and domineering. Her life reading attributed this tendency to the fact that she had been a school teacher in early Ohio, and had held a position of authority in Palestine and India incarnations.

A young boy showed, from early childhood, an extremely argumentative turn of mind and displayed acute reasoning powers. These traits took rise from an incarnation as a man of law at the time of the establishing of trail by jury by Alfred the Great, and from another incarnation as a judge in Persia.

A woman of mystic, quietistic tendencies had been in the life previous to the present the head of a religious retreat in the early nineteenth century. A wealthy young man, whose escapist drinking was the despair and disgrace of his distinguished family, had laid the basis for the weakness in a dissolute experience during the Gold Rush.

Hundreds of instances similar to these are to be found in the life-reading files. Anyone familiar with the Psychology of Individual Differences and the problems with which it deals, cannot but recognize that this material, if true, gives a whole new depth and comprehensiveness to Differential Psychology.

The crux of the matter is this: Modern psychology assumes that differences between human beings are determined primarily by the genes of the parents and secondarily by environmental influences. By the reincarnationist view, however, heredity and environment are themselves the result of past life karmic determinants, and every quality of the soul is self-earned rather than parentally transmitted.

There is a certain fallacy in the theory of heredity that is not generally recognized. By the hereditary view, it is presumed that phenomena of a mental order can be created by phenomena of a biological order. Remembering Einstein’s engaging and ingenuous audacity (“How did you discover relativity?” “By challenging an axiom!”), it is perhaps worthwhile to challenge the fundamental assumption on which the hereditary theory is based. Man’s knowledge of the mind-body relationship is still in its infancy, to be sure; yet it seems more credible, and psychologically more sound, to believe that phenomena of a mental order must in large part be caused by previous phenomena of a mental order also. “All that you are,” said Buddha, “is the result of what you have thought.” In that excellent and psychologically rigorous religion, Buddhism, reincarnation is, of course, a cardinal teaching; Buddha taught that a man’s qualities are the result of his modes of thinking and acting in past lifetimes. Merely from a mechanistic point of view it seems reasonable to argue that only repeated personal effort can account for personal capacity. If this is so, then it is inferentially necessary that the differences between human endowment in the present are due to differences of human effort in the past.

Ralph Waldo Emerson—an avid student of Eastern thought and devoted reader of the Bhagavad-Gita, the Hindu bible—understood this concept thoroughly. It appears by implication in much of what he wrote, but becomes particularly explicit in his essay on experience. The essay begins:

“Where do we find ourselves? In a series of which we do not know the extremes, and believe that it has none.

“We awake and find ourselves on a stair; there are stairs below us which we seem to have ascended; there are stairs above us, many a one, which go upward and out of sight. But the Genius which according to the old beliefs stands at the door by which we enter, and gives us the Lethe to drink, that we may tell no tales, mixed the cup too strongly, and we cannot shake off the lethargy now at noonday.”

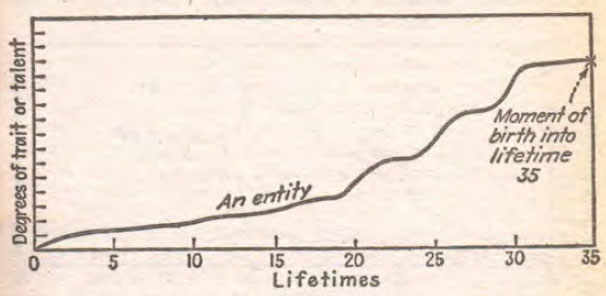

Emerson’s use of the word “series” suggests the evolutionary nature of all life; his image of the stairs is a particularly graphic representation of how human capacities seem to advance upward as lifetimes progress. The growth of traits and talents does seem to exhibit, in the Cayce data, a kind of continuity that is stair-like in nature. This fact suggests the name Continuity Principle, which can be illustrated in the following manner:

The preceding table portrays how an entity gradually advances in the acquisition of any trait (such as honesty, courage, unselfishness) or talent (music ability, artistic faculty, mathematical insight, etc.) If we were to trace the progress of the entity here represented with respect to musical ability, for example, we might see that in Lifetime 1 he began to use a rudimentary musical instrument, perhaps a reed. In Lifetimes 2, 3, and 4 he used other musical instruments of later culture epochs, increasing gradually the faculties of pitch, rhythm, melodic memory, and so forth, which are the components of what we call musical talent. Finally, Lifetime 35, he was “born with” extraordinary talent or even what is known as genius.

The preceding table portrays how an entity gradually advances in the acquisition of any trait (such as honesty, courage, unselfishness) or talent (music ability, artistic faculty, mathematical insight, etc.) If we were to trace the progress of the entity here represented with respect to musical ability, for example, we might see that in Lifetime 1 he began to use a rudimentary musical instrument, perhaps a reed. In Lifetimes 2, 3, and 4 he used other musical instruments of later culture epochs, increasing gradually the faculties of pitch, rhythm, melodic memory, and so forth, which are the components of what we call musical talent. Finally, Lifetime 35, he was “born with” extraordinary talent or even what is known as genius.

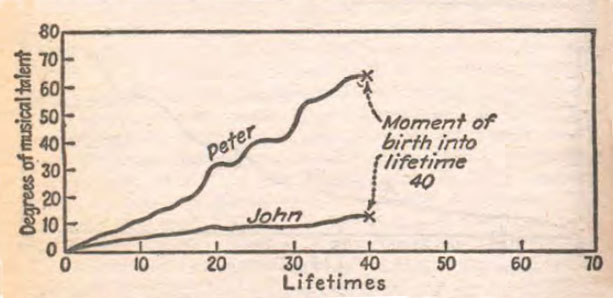

The new depth given by this concept to the Psychology of Individual Differences is shown still more completely by the following table in which John and Peter are compared in musical talent from the moment of birth into Lifetime 40.

The chart reveals that the entity called Peter has devoted himself to music for many lifetimes past. The entity called John has given some attention to music, but not much. On our arbitrary scale of degrees of musical talent, say that 60 is the equivalent of “genius.” At the moment of birth, Peter, then, is a musical genius; John, merely the possessor of a simple degree of talent. Similar diagrams could be drawn with respect to any human capacity, and thus the basis for a science of Individual Differences is revealed; the reason for differing human endowments at birth becomes clear.

Unfortunately, many persons who accept the karmic idea tend to think of karma only in terms of punishment and suffering. But it must be remembered that karma literally means action, which is a neutral word. Everything in the manifest universe has its polarity, or its positive and negative aspects; karma is no exception. Obviously, action can be evil or good, selfish or selfless. If conduct is good, there is nothing to prevent it from continuing; this proceeds by natural growth, and can, as suggested, be called the Continuity Principle of karma. If, however, conduct is flagrantly evil or impure, it must be corrected; this proceeds by the law of action and reaction, and might be called the Retributive Principle of karma.

Unfortunately, many persons who accept the karmic idea tend to think of karma only in terms of punishment and suffering. But it must be remembered that karma literally means action, which is a neutral word. Everything in the manifest universe has its polarity, or its positive and negative aspects; karma is no exception. Obviously, action can be evil or good, selfish or selfless. If conduct is good, there is nothing to prevent it from continuing; this proceeds by natural growth, and can, as suggested, be called the Continuity Principle of karma. If, however, conduct is flagrantly evil or impure, it must be corrected; this proceeds by the law of action and reaction, and might be called the Retributive Principle of karma.

By the Retributive Principle we are brought back through the painful equilibrating force of karma to the narrow path of self-perfection. But by the Continuity Principle we make tranquil, uninterrupted progress along that selfsame path. Like the chambered nautilus, we build ourselves, as the lifetimes pass, more stately mansions for the soul. And at length we are free.

Excerpt from Many Mansions

Posted in Other Topics, Past Life Therapy, Reincarnationwith 1 comment.

Very revealing !