A Higher Dimensional Reality

Based on the work by Michael Talbot – Beyond The Quantum

Based on the work by Michael Talbot – Beyond The Quantum

“I would say that in my scientific and philosophical work, my main concern has been with understanding the nature of reality in general and of consciousness in particular as a coherent whole, which is never static or complete but which is an unending process of movement and unfoldment….” ~ (David Bohm: Wholeness and the Implicate Order)

In 1951, David Bohm wrote a classic textbook entitled Quantum Theory, in which he presented a clear account of the orthodox, Copenhagen interpretation of quantum physics. The Copenhagen interpretation was formulated mainly by Niels Bohr and Werner Heisenberg in the 1920s and is still highly influential today. But even before the book was published, Bohm began to have doubts about the assumptions underlying the conventional approach. He had difficulty accepting that subatomic particles had no objective existence and took on definite properties only when physicists tried to observe and measure them. He also had difficulty believing that the quantum world was characterized by absolute indeterminism and chance, and that things just happened for no reason whatsoever. He began to suspect that there might be deeper causes behind the apparently random and crazy nature of the subatomic world.

In 1952, a year after having discussions with Einstein, Bohm published two papers sketching what later came to be called the causal interpretation of quantum theory which, he said, “opens the door for the creative operation of underlying, and yet subtler, levels of reality”. He continued to elaborate and refine his ideas until the end of his life. In his view, subatomic particles such as electrons are not simple, structureless particles, but highly complex, dynamic entities. He rejected the view that their motion is fundamentally uncertain or ambiguous; they follow a precise path, but one which is determined not only by conventional physical forces but also by a more subtle force which he calls the quantum potential. The quantum potential guides the motion of particles by providing “active information” about the whole environment. Bohm gives the analogy of a ship being guided by radar signals: the radar carries information from all around and guides the ship by giving form to the movement produced by the much greater but unformed power of its engines.

The quantum potential pervades all space and provides direct connections between quantum systems. In 1959, Bohm and a young research student Yakir Aharonov discovered an important example of quantum interconnectedness. They found that in certain circumstances electrons are able to “feel” the presence of a nearby magnetic field even though they are traveling in regions of space where the field strength is zero. This phenomenon is now known as the Aharonov-Bohm (AB) effect, and when the discovery was first announced many physicists reacted with disbelief. Even today, despite confirmation of the effect in numerous experiments, papers still occasionally appear arguing that it does not exist.

In 1982 a remarkable experiment to test quantum interconnectedness was performed by a research team led by physicist Alain Aspect in Paris. The original idea was contained in a thought experiment (also known as the “EPR paradox”) proposed in 1935 by Albert Einstein, Boris Podolsky, and Nathan Rosen, but much of the later theoretical groundwork was laid by David Bohm and one of his enthusiastic supporters, John Bell of CERN, the physics research center near Geneva. The results of the experiment clearly showed that subatomic particles that are far apart are able to communicate in ways that cannot be explained by the transfer of physical signals traveling at or slower than the speed of light. Many physicists, including Bohm, regard these “nonlocal” connections as absolutely instantaneous. An alternative view is that they involve subtler, nonphysical energies traveling faster than light, but this view has few adherents since most physicists still believe that nothing can exceed the speed of light.

“On this stream, one may see an ever-changing pattern of vortices, ripples, waves, splashes, etc., which evidently have no independent existence as such. Rather, they are abstracted from the flowing movement, arising and vanishing in the total process of the flow. Such transitory subsistence as may be possessed by these abstracted forms implies only a relative independence or autonomy of behaviour, rather than absolutely independent existence as ultimate substances.”

Is The Implicate Order Holographic?

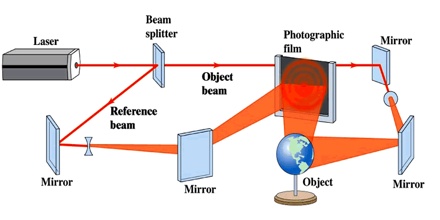

Another metaphor Bohm used to illustrate the implicate order is that of the hologram. To make a hologram a laser light is split into two beams, one of which is reflected off an object onto a photographic plate where it interferes with the second beam.

The complex swirls of the interference pattern recorded on the photographic plate appear meaningless and disordered to the naked eye. But like the ink drop dispersed in the glycerin, the pattern possesses a hidden or enfolded order, for when illuminated with laser light it produces a three-dimensional image of the original object, which can be viewed from any angle. A remarkable feature of a hologram is that if a holographic film is cut into pieces, each piece produces an image of the whole object, though the smaller the piece the hazier the image. Clearly the form and structure of the entire object are encoded within each region of the photographic record.

The complex swirls of the interference pattern recorded on the photographic plate appear meaningless and disordered to the naked eye. But like the ink drop dispersed in the glycerin, the pattern possesses a hidden or enfolded order, for when illuminated with laser light it produces a three-dimensional image of the original object, which can be viewed from any angle. A remarkable feature of a hologram is that if a holographic film is cut into pieces, each piece produces an image of the whole object, though the smaller the piece the hazier the image. Clearly the form and structure of the entire object are encoded within each region of the photographic record.

Bohm suggests that the whole universe can be thought of as a kind of giant, flowing hologram, or holomovement, in which a total order is contained, in some implicit sense, in each region of space and time. The explicate order is a projection from higher dimensional levels of reality, and the apparent stability and solidity of the objects and entities composing it are generated and sustained by a ceaseless process of enfoldment and unfoldment, for subatomic particles are constantly dissolving into the implicate order and then recrystallizing.

The quantum potential postulated in this causal interpretation corresponds to the implicate order. But Bohm suggests that the quantum potential is itself organized and guided by a superquantum potential, representing a second implicate order, or superimplicate order. Indeed he proposes that there may be an infinite series, and perhaps hierarchies, of implicate (or “generative”) orders, some of which form relatively closed loops and some of which do not. Higher implicate orders organize the lower ones, which in turn influence the higher.

Bohm believes that life and consciousness were enfolded deep in the generative order and are therefore present in varying degrees of unfoldment in all matter, including supposedly “inanimate” matter such as electrons or plasmas. He suggests that there is a “proto intelligence” in matter, so that new evolutionary developments do not emerge in a random fashion but creatively as relatively integrated wholes from implicate levels of reality. The mystical connotations of Bohm’s ideas are underlined by his remark that the implicate domain “could equally well be called Idealism, Spirit, Consciousness. The separation of the two–matter and spirit–is an abstraction. The ground is always one.”

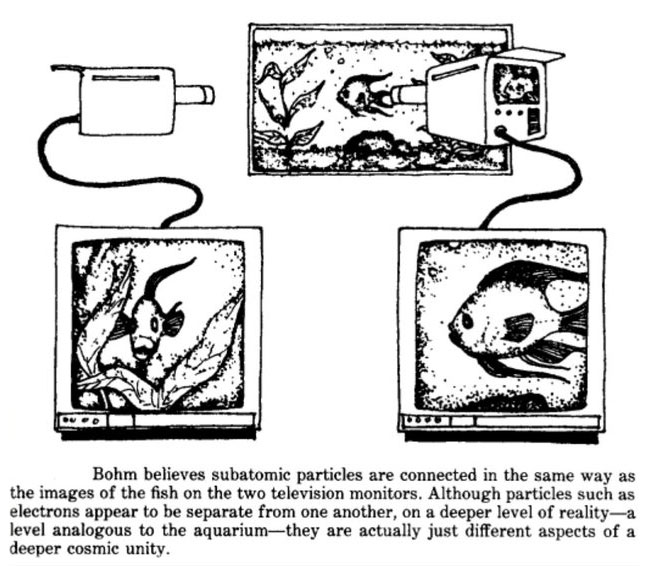

So Bohm concludes that existence includes a nonlocal level of reality beyond the quantum. That is, what we perceive as separate particles in a subatomic system are not really separate at all, but on a deeper level of reality are merely extensions of the same fundamental something. He identifies the explicate order as the level we inhabit and the implicate order as the level in which separateness vanishes and all things appear to be part of a unbroken whole. An example of this he provides in the “aquarium model” illustrated below.

So when we look at two subatomic particles, we are looking at two different images of the same thing but at different angles creating the illusion of separateness. Put another way, the images on the television screens are really two-dimensional projections (or facets) of a three-dimensional reality. Given that two three-dimensional entities such as the photons in the Eistein-Podolsky-Rosen experiment can behave as if they are part of an equally startling and unbroken wholeness, it follows, says Bohm, that our own three-dimensional world is therefore the projection of a still higher and multidimensional reality.

So when we look at two subatomic particles, we are looking at two different images of the same thing but at different angles creating the illusion of separateness. Put another way, the images on the television screens are really two-dimensional projections (or facets) of a three-dimensional reality. Given that two three-dimensional entities such as the photons in the Eistein-Podolsky-Rosen experiment can behave as if they are part of an equally startling and unbroken wholeness, it follows, says Bohm, that our own three-dimensional world is therefore the projection of a still higher and multidimensional reality.

Can Bohm’s Theory Explain The Double-Slit Experiment?

When a photon seems to go through both slits in the double-slit experiment at once, this confounds our commonsense because we insist upon thinking of the photon as possessing a single location in space and time. However, if Bohm is correct, this is simply not the case. Under certain circumstances the three-dimensional projection of the photon might appear to have a specific location. But because the photon is really a projection of a single and higher-dimensional reality, it is not rigidly confined to the rules of our third dimensional universe. For example, if our apparent separation from the objects we observe is merely an illusion of the explicate order, we are ultimately no more separate from them than adjacent designs on a piece of carpet. It is important to note that the apparent effect an observer has on the quantum system he or she is observing does not imply that some sort of causal interaction is taking place between the two. In other words, a interaction isn’t happening just due to observation but rather is due to the effect being abstracted or ‘pointed out’ by our mode of description but, in short, quantum particles are merely all projections of a deeper, nonlocal reality. Given that all objects that we know are constructed out of quanta, from Sequoia tress to quasars, if Bohm’s theory is correct, it means that all things in the universe are infinitely interconnected. Or as Bohm puts it, “Everything interpenetrates everything.” If such a point of view is correct it would give new meaning to Blake’s advice “to see a world in a grain of sand”.

Mind Connections

Perhaps the most intriguing aspect of Bohm’s theory is how it might apply to our understanding of the human mind. As he sees it, if every particle of matter interconnects with every other particle, the brain itself must be viewed as infinitely interconnected with the rest of the universe. Bohm believed that such a mind-boggling interconnectedness would even shed light on the phenomenon of consciousness itself.

To begin with, one of the great unsolved puzzles of all time is the so-called mind-body problem. Simply stated, the mind-body problem can be summed up in a single question: Is there any fundamental difference between the mind and the body? This is just another way of saying, What is consciousness? Is consciousness simply the sum of what is going on in our brains? The standard answer of science is that there is no ultimate distinction between mind and body. Consciousness is synonymous with the brain, and when the brain dies all of those things that we associate with consciousness—self-awareness, perception, acts of understanding, and so on—die with it. The opposing point of view is that we are more than the sum of our parts and when we die some aspect of our consciousness survives and goes on. If we accept this point of view, the question then becomes, What is that something which survives?

One great thinker who articulated with unusual clarity what that something might be was the seventeenth-century French philosopher and mathematician, Rene Descartes. Descartes described matter as “extended substance”. Evidently, by “extended substance” Descartes meant that matter is something that is made up of distinct forms and exists in space. In contrast to this he referred to consciousness as “thinking substance,” and by drawing such a sharp distinction between the two, clearly implied that the various distinct forms that appear in thought do not have extensions or separations in space as we know it.

Bohm is particularly taken with this assessment and points out that Descartes’ distinctions between consciousness and matter are precisely the same distinctions that he makes between the implicate and explicate order. Bohm suggests, for example, that one consider the process that goes on when one listens to a beautiful piece of music. At any given moment only a single note might be played, but somehow the mind connects each note into a sensation of wholeness. As Bohm sees it, one does not experience the actuality of the whole piece of music by holding onto the past or comparing any given note with one’s memories of previous notes. Rather, each note causes an active transformation of what came earlier. As Bohm states, “One can thus obtain a direct sense of how a sequence of notes is enfolding into many levels of consciousness, and of how at any given moment, the transformations flowing out of many such enfolded notes interpenetrate and intermingle to give rise to an immediate and primary feeling of movement.” Bohm further suggests that this is one way that each of us experiences firsthand the holographic of implicate nature of consciousness. This is not the only evidence available to us that suggests that consciousness is holographic.

Karl Pribram also proposed a holographic model of consciousness. To support his conclusion Pribram cites evidence that memory does not seem to be stored in any particular localized part or individual cell in the brain but instead somehow seems to be distributed over the whole brain. Various experimental discoveries over the years have proven the theory that the structures responsible for memorizing and remembering things are not located in any single part of the brain but are distributed over the brain as a whole in much the same way that the image of a hologram is enfolded in all of its parts.

The Universe As An Unbroken Whole

Bohm believes that even life itself has aspects of an implicate order written all over it. For example, according to conventional biological understanding, a seed contains within it very little of the actual material substance that will ultimately be contained in the plant that it becomes. Most of the substance of the plant comes from the soil, water, air, and sunlight. According to modern theories, what the seed does contain is information, in the form of DNA, and somehow it is this information that directs the environment to form a corresponding plant.

However, as the plant is formed, maintained, and dissolved by the exchange of matter and energy with its environment, at what point can we say that there is a sharp distinction between what is alive and what is not? Similarly, when a molecule of carbon dioxide suddenly crosses a cell boundary into a leaf, it does not suddenly come alive. Nor does a molecule of oxygen suddenly die when the leaf expels it into the atmosphere. As Bohm sees it, this lack of distinct boundaries between what is alive and what is not once again underscores the inadequacy of a strictly mechanistic approach to the universe. Instead of trying to divide the universe into parts that are alive and parts that are not, a better approach might be to view the universe as an unbroken whole, a totality into which both living and nonliving things are constantly enfolding and unfolding.

As Bohm sees it, if the universe is nonlocal at a subquantum level, that means that reality is ultimately a seamless web, and it is only our own idiosyncrasies that direct us to divide it up into such arbitrary categories as mind and body. Thus, consciousness cannot be considered as fundamentally separate from matter, any more than life can be considered as fundamentally separate from non-life. Both are secondary and derivative categories and both are enfolded in a higher common ground.

The Paranormal Becomes Possible

Could this interconnectedness produce phenomena resembling ESP and the paranormal? Bohm believed that if the paranormal exists, “it can only be understood through reference to the implicate order, since in that order everything contacts everything else and thus there is no intrinsic reason why the paranormal should be impossible”.

Bohm does believe that someday it will be possible for people to perceive the higher and multidimensional common ground where consciousness and matter are no longer separate and in essence become a sort of group mind. Where or how this higher ground may be perceived, Bohm does not know and says only that it is a “deeper and more inward actuality” that is “neither mind nor body but rather a yet higher-dimensional actuality”.

Infinite Dimensional Levels

Bohm cannot say how many dimensions this higher actuality might possess; however, he boldly suggests that at the superholographic level the universe may have as many dimensions as there are subatomic particles in our third-dimensional universe, a staggering 1089. And even then, Bohm asserts, this superholographic level may still be a “mere stage” beyond which is “an infinity of further development”.

In Conclusion

What other characteristics might typify such a higher, multidimensional common ground? Bohm cautiously states, “It is vast, rich, and in a state of unending flux of enfoldment and unfoldment, with laws most of which are only vaguely known”. However, he then goes on to add that because consciousness and matter, life and non-life, are all one in this common ground, the totality itself must be seen as possessing these qualities. In other words, nature itself must be viewed as a living organism, and given the diversity and richness of forms that the superhologram perpetually pours forth, it is even safe to conclude that it is “purposive” and possesses “deep intentionality”. All of the creativity and insight that we ourselves experience must also be seen as derivative of this common ground, and thus in a sense it seems that nature has made us seek her. Perhaps that is why there is a deep drive in all of us to understand the universe. It would no longer be correct to speak of the multidimensional level of the universe as a material plane. Rather, Bohm concludes, “it could equally well be called Idealism, Spirit, Consciousness. The separation of the two—matter and spirit—is an abstraction. The ground is always one”.

Posted in Other Topics, Science For The New Agewith comments disabled.