Three Lifetimes Lived

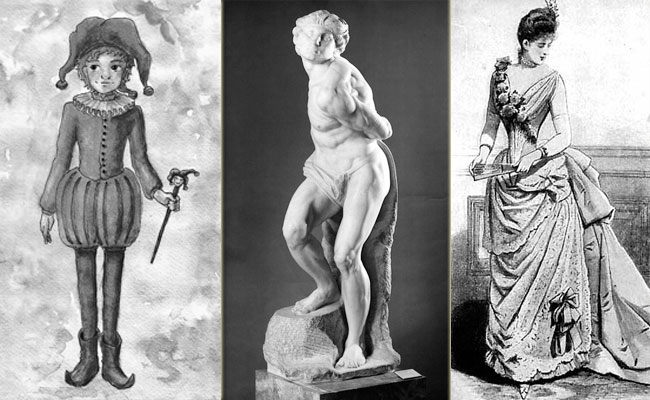

The Court Jester, the Roman, and the Victorian Lady

The Court Jester, the Roman, and the Victorian Lady

by Barbara Hand Clow

“I remember exactly what it felt like to be an infant with clenched fists and kicking feet. All things were primal; emotions and actions were one. As I clenched my fist and pushed it out while kicking  my feet, energy moved in my system freely, and my system responded automatically. There was no fear; there was no will or self-awareness. There was no difference between my self and the things around me; this was ecstasy.

my feet, energy moved in my system freely, and my system responded automatically. There was no fear; there was no will or self-awareness. There was no difference between my self and the things around me; this was ecstasy.

I’m dancing in court! My tunic is tight around my waist and swirls into a skirt of bell-tipped points. It is made of green and gray felt, as are my shoes. My outfit looks like fish scales, and the bells ring as I jump and stomp my feet. The Gothic ceiling above me is high and ornate, and the arches are carved of brightly painted wood. Everything is carved, and painted red, green, yellow, and blue. There are lots of people around me, and I’m moving so fast. I am highly trained as a dancer and I am kicking my feet, bending over, and swooping with my hands. I’m twirling around fast, stomping my feet hard on the floor. The pointed shoes with bells are moccasins, and I’m thumping my heels on the tile. Music rings to the high ceilings as I strike my tambourine on my knee, shaking it and stomping hard and whirling. I am almost out of balance as I swirl close to the people laughing merrily.

There are beautiful ladies here, and I pay a lot of attention to them. Dangerously close, I smile at them. They pay no attention to me, but I’m free to look at them all I want. I can look at anybody as long as I keep dancing with the rhythm of the musicians. I’m fourteen, and my eyes are darting around my head because there is so much to see.

I leave when the dancing ends. The musicians file out as I dance along behind them. There are ten or twelve of them, and they are all older than I. We pass through a beautiful hallway with highly decorative green, red, and yellow floor tiles and carved wainscoting on the walls. The ceiling is very high with vaulting arches that are carved and painted in bright colors. We step down into a low archway to enter the servants’ quarters. Now the hall is narrow, the floor is wooden, and down a few stairs is the servants’ kitchen. Before going in, the musicians put their instruments down as I take off my pointed hat, heavy with bells. The planked table is long, with a bench on each side. We sit down and await our supper; we will be served soon after entertaining the court.

The kitchen is long and narrow with a high ceiling of dark wood. Its walls are stone, its beams are heavy, and it feels like a church. Everyone is in a festive mood, and we laugh and talk about the scenes in the court. The women musicians wear low-necked dresses for the pleasure of the Count and they tease me because I stare at their breasts pushed up high. They laugh and pinch my cheeks as we drink wine out of pewter-stemmed goblets. Pork roast slathered with sticky marmalade and surrounded by thick carrots is carried in on large platters. We soak the thick black bread in gravy. Then fruit is brought in, piled high in heavy bowls.

Later, I stumble down a narrow hallway with stone floors to the place where I sleep. The arches are triangular and made of wood, and the walls are stucco with heavy tapestries hanging on them to help absorb the relentless cold and dampness. The vaulted ceilings are dimly visible in the light from the sconces on the walls. The heavy wooden doors to my room have large iron rings and they creak when I open them. I enter and walk to the window, pushing aside the heavy fabric that covers it. The window is small with a thick sill. The sunlight outside is very bright, and the light sparkles in the bubbly glass. I open the window, and find that the walls of stone are so thick that I cannot reach through to the outside wall. It is the sixteenth century in Leipzig, and this building is already more than four hundred years old. There are bars in the opening. As I look out, I see yellow grass and intensely green trees. My thoughts turn to my studies.

My room has a small cot close to the floor and a dark wooden chair with a high back. My trunk has a few clothes in it, and there is a large leather-bound book on top. I don’t spend much time in here because the books for the house are in the Count’s library. The heavy book on the trunk is a Bible, and I open it. It begins with “Und der Lacht” drawn in ornate red and blue letters, but I do not like it. I like the books in the library better. This room is not where I spend my time. I like to dance in the court and study in the large library, and my name is Erastus Hummell.

As I lie in my crib in the fifth month of this lifetime, I feel Erastus as I swing my feet around and bump them hard on the side of my crib. I wonder if there were other ways to awaken this Renaissance jester in my muscles and bones to counteract the paralysis I feel in the air. During those early months, when my new life as Barbara organized my nervous system, I re-experienced Erastus as a systemic ecstasy. The present incarnation was thickening and threatening to overwhelm my fragile thread to total consciousness. This time it was the jester, my inner clown, who lit the candle of my spirit when I was temporarily blinded by a rare eye disease at five months.

My eyes were sealed shut for four days and nights. I was left alone in my crib, and no one seemed to be aware of my terror as my world sank into blackness. This was too much for my mother to cope with, and the nurses did not care. I was just left in my crib in the midst of inexplicable blackness, as if the gates of Hades had opened and engulfed me! Within a few hours, I was gripped by massive anxiety and terror, a terror so great that it seemed I lay awake for the entire four days and nights. All my deepest inner fears from my previous lives ripped through my system, accessing terrors so early and on a scale so intense that my will to live was challenged too soon. All the voices began echoing from the deepest recesses of my brain while I lay helpless and sightless in my crib.

They are taking me down the hallway of a prison. The cells are crowded with people, and others lie in the halls, sleeping in their rags and fleas. I cannot imagine who they all are. The soldiers holding me stumble over them and kick them, yet they do not rise out of their stupor. I thought they’d put me in one of those cells but they don’t. They pull my limbs so hard that I worry the sockets will not hold, as they take me down to a round room at the end of the hallway. I am a small man of twenty years. I’ve been brought into a prison in Rome and I’m frightened by the city. I’m from the country. This place smells, and look at those bars! The guards lead me into the round room. Inside there is only a wooden table covered with surgical instruments, and I know what they’re going to do: They’re going to castrate me! I only realized this when I passed through the barred doors. I start thrashing. My throat closes and I am suffocating. The light turns to thick gray fog, and adrenaline shoots through every cell of my body; my senses are obliterated. I’m pushing and shoving like a cornered wild animal against the five or six soldiers. I bite and I snap my head back when I see the golden blond hair and vacuous blue eyes of one soldier, who is enjoying it. The others don’t want to do this to me. But the little blond one leers at me as I try to bite him and claw him. It is hopeless.

As I lie on the table, I also feel like I am above my body watching it. They have removed my pants, and my genitals are exposed. I feel a naked terror as my mind is exploded by bright light surrounded by a deafening humming; existence ceases. A man comes in wearing a long white tunic, and he picks up a thin knife about four inches long. I see it from the outside, but not completely, and the hot pain is incredible! My pinned-down legs hurt almost as badly because I can’t move to release the shock in them. He cuts off one ball, and the blood spurts out like thick warm water. My sap splashes on the floor, my ichor. Then a sickening but relieving passivity overwhelms my mind. They lift me and haul me out of the room quickly and put me in one of the cells in the hall. There is a woman in the cell, and I collapse next to her, writhing in pain, with my knees doubled up. She caresses my back with long slow strokes as she stares at the ceiling with no expression on her face. She strokes my back until I black out.

No one stroked me during my blindness in this life. Another memory welled up from the deep during my blindness: the memory of my lifetime as the Victorian Lady from just before my birth in 1943.

First, I begin to merge into her body, but it is too close; she is my shadow. Like having two bodies in one, I can see her sagging brown-eyed face drifting through my reality. Just as I always see my own mother’s face when I look in the mirror, so also I see myself as her face from long ago. The drifting is an agony of feathery images moving like dust that I cannot grasp. As if only compressed terror could move me into her memory, I fight not to know the ultimate terror; I am going to suffocate in the spinning trap of a female spider.

As if only a female can know the full horror of the silken thread spun endlessly out of the female spider’s body, in my blindness I push frantically against my arachnid prison crib. My breathless nightmare mercilessly moves out of soft gray pillows of throat-catching, sticking saliva into the black pitiless tumbling.

The last picture my sightless brain activated was my crib spun into the nest of the female black widow, and then I became her. I broke all the rules of karma when I passed into her and became her. I became the woman who died eleven years before I was born in 1943.

The Victorian shadow speaks now. . . . I am a tall, bony woman with slightly curled medium-length brown hair. My skin is soft and loose, my nose is large with a bump on the ridge, and my eyes never focus directly on anyone. I wear a light-blue wool cashmere sweater with a brown cardigan pulled over it, and my wool skirt is brown and beige plaid from Scotland. I am dowdy, and I am almost forty years old. I will never throw my brown sweater out because it makes me feel secure, and I wear blue stockings with ordinary brown leather shoes. I stand on a large Oriental rug in an elegant wood-paneled room filled with heavy furniture. Everyone in the room is dressed in heavy winter clothes, and they are all very rich.

I look out the bay window to see a street scene of two and three story brownstones, as well as elegant buildings made of gray cut stone with small yards set off by lacy wrought iron fences. The wavy-glassed windows are cold and damp. Today there is no snow, yet the earth is frozen deep. There are a few fall leaves on the ground blowing around or frozen onto stiff grass. Chevrolets, Packards, and a few Fords are parked on the street.

It is Chicago in November, and my name is Leonore Brewer Cudahy. This house is a large corner house built in 1883; it is rigid and unbending like my relatives who’ve lived here all these years. This house is like a prison, but I am not allowed to say that to anyone. My soul is imprisoned in my body as my body is in this house. There is a clock on the mantel that says 9 a.m. I walk into the library across the hallway and see a New Yorker on the table; the date is November 17, 1928. I walk into the hallway to look in the mirror. I see my mother’s face instead of my own; I always do. Mother died when I was seventeen, just when I wondered if I was beautiful or not. Hers is a haughty face framed in a velvet feather-plumed hat, and behind that face, I see my own. I don’t like to see my face because I’m unhappy, so I look away. There is much to read in the striations of my eyes; it’s like gazing into a smoky quartz crystal ball.

I am the Victorian woman who is not around her children very much. Everything in this house is controlled by my husband’s mother and the servants, and of course, my husband. I can’t cook for my children, nor arrange their rooms, and the chauffeur drives them wherever they go. My mother-in-law criticizes me because I want to spend time with them and relate to them. It is as if I am toxic to my own children! She makes my children side with her family by keeping me away from them. I am passive and I don’t fight it. I let it all happen to me because the cells deep within my body are cancerous. My motherly feeling about my children does not matter to her. What matters is that the way of life that has always been will continue. She has absolute financial control over my husband. He does business as she pleases. This house feels like it belongs to her, since she owns everything. She controls all the wealth, and we exist on her gifts.

While eating a very formal dinner at the big table, I look at the children. They’re groomed and dressed up, and having a good time. I feel very weak, as if my children have more power than I do. I know why I feel weak. I’m sick, very sick. When I look in the mirror, I feel as if my reflection shows that I’m sick. It’s as if I’ve produced the children for somebody else. I love them so much, yet I feel trapped inside and I can’t reach out to them. I feel that if I tried to reach them, they would reject me because they’ve been conditioned to be cold toward me. I remember the first one, Michael, wearing all white when he was just an infant. I was twenty-four years old, but a nurse was appointed to take care of my baby. Everyone was always so afraid of germs! I would hold him for a little while, and then the nurse would take him away. Now, I sense this was not a good thing. I remember holding him when I was all dressed up. He was also dressed up, and I remember handing him back to the nurse. I was going out to dinner. Now it strikes me that this was not right but I can’t do anything about these things. My sense of life is holding my arms out and releasing my children to someone else. I’m dressed up as usual and I feel deaf and listless, and all my responses are automatic. I like the lake a lot, and I just had a memory of sailing in a boat. There are times when I sense a feeling of nature, but mostly I am in stone buildings where I can’t breathe.

Drifting, drifting, it is so oppressive. How can anyone stand to drift? I am lying still on my back holding a blanket, and the oppressiveness has gone on so long now that I stop drifting and just fall. I still cannot see. I fall softly like endless snow right back into my death in my last life. It is against all the rules of human karma, yet if a small baby suffers enough, it will die previous deaths in order to find a new path. This time I had to break through the passivity of the Victorian Woman in order to even activate my lungs and utter my first cry in this life.

Lying in my bed, I await my end with resignation. The cancer has finally won its battle. I’m forty-three years old, and I no longer care. All I wish is that my daughter would go away. Her cornflower blue eyes make me feel so bad that I choke. I am leaving her behind, and I wonder if anyone will hear me softly weeping. I wanted to be close to her, but I wasn’t. Now she stands there like a moment lost in time. She’s ten and she knows I’m dying. Like an animal, all I want to do is crawl away into a pit, but I can’t reject her now. I weigh only eighty pounds. She has light all around her. In this moment when she’s with me, she decides she will never live! She ingests my passive deathliness as if the cancer will start when the female hormones are later activated in her body. I am aware as she decides to die in her mind, and I know she will never even know the passion I felt when I was young.

We are both surrounded by silence, since she feels I am the only life she has ever known. As the life passes out of me, a part of her dies too. She knows I hated everything around me, so all that is left behind me are the ways of life we lived. Her soul tuned in to who I really was, and she knows that all that remains are the deathly structures. She dies with me, and later, society becomes her life. The light around her terrifies me. I see her higher self leave her that morning. I can go to the light, but she will live her life without it.

So when my hour of death arrived, I could not leave her. I was caught, and I hovered near Earth until I returned as Barbara to find my daughter again.”

Excerpt from The Mind Chronicles: A Visionary Guide Into Past Lives

Posted in Past Life Therapywith comments disabled.