The Egyptian

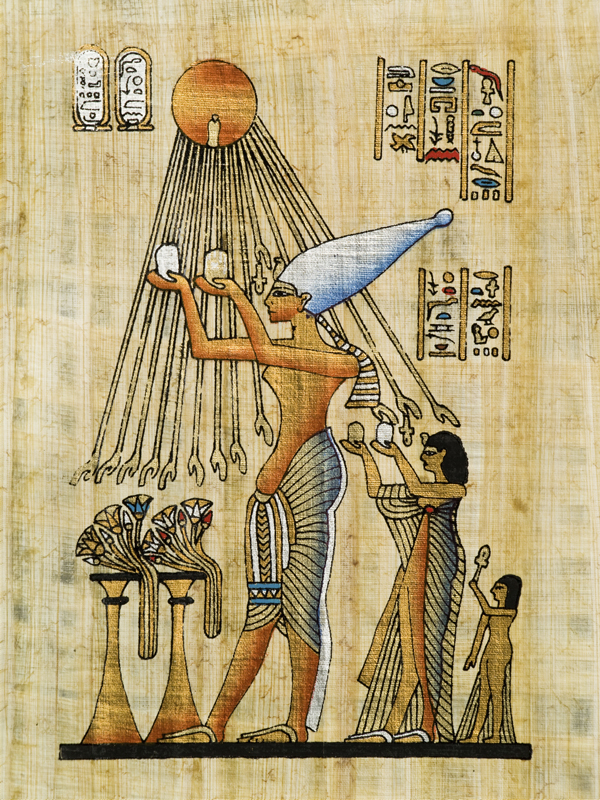

“But Ammon is a hateful god, and his priests have kept the people in darkness for too long and stifled every living thought, until no one dares say a word without Ammon’s leave. Whereas Aton offers light and a life of freedom—a life without fear—and that is a great thing, a very great thing, my friend Horemheb.” ~ Sinuhe, the Egyptian

by Mika Waltari

The Egyptian is the full-bodied re-creation of an era hitherto untapped by fiction. As such it is rich with fresh veins of fascinating lore. Entirely authentic, it is written with a literary excellence of which few contemporary historical novels can boast.

excellence of which few contemporary historical novels can boast.

The story of The Egyptian is rolled out on a tremendous canvas. Set in Egypt, more than a thousand years before Christ, it encompasses all of the then-known world. It is told by Sinuhe, physician to the Pharoah, and is the story of his life. Through his eyes are seen innumerable characters, full drawn and covering the whole panorama of the ancient world. Events of war, intrigue, murder, passion, love, and religious strife are revealed as Sinuhe describes his often brilliant, often bitter life.

There is real grandeur to The Egyptian. It has the broad sweep of truly major fiction, a powerful narrative pace coupled with intense human interest. It is the astonishing triumph of a great creative imagination.

[Editor’s note: I don’t consider this to be imagination or fiction as I believe Mika draws on a past life experience or has tuned into its events to provide the narrative.]

The author, Mika Waltari, is probably the most famous living writer in his native Finland. His book, already an enormous success in Europe will be recognized here, too, as a magnificent epic. – Book Of The Month Club (inside jacket)

Book I – The Reed Boat

I, SINUHE, the son of Senmut and of his wife Kipa, write this. I do not write it to the glory of the gods in the land of Kem, for I am weary of gods, nor to the glory of the Pharaohs, for I am weary of their deeds. I write neither from fear nor from any hope of the future but for myself alone. During my life I have seen, known, and lost too much to be the prey of vain dread; and, as for the hope of immortality, I am as weary of that as I am of gods and kings. For my own sake only I write this; and herein I differ from all other writers, past and to come.

I, SINUHE, the son of Senmut and of his wife Kipa, write this. I do not write it to the glory of the gods in the land of Kem, for I am weary of gods, nor to the glory of the Pharaohs, for I am weary of their deeds. I write neither from fear nor from any hope of the future but for myself alone. During my life I have seen, known, and lost too much to be the prey of vain dread; and, as for the hope of immortality, I am as weary of that as I am of gods and kings. For my own sake only I write this; and herein I differ from all other writers, past and to come.

I begin this book in the third year of my exile on the shores of the Eastern Sea, whence ships put out for the land of Punt, near the desert, near those hills from which stone was quarried to build the statues of former kings. I write it because wine is bitter to my tongue, because I have lost my pleasure in women, and because neither gardens nor fish pools delight me any more. I have driven away the singers, and the sound of pipes and strings is torment to my ear. Therefore, I write this, I, Sinuhe, who make no use of my wealth, my golden cups, my ebony, ivory, and myrrh.

They have not been taken from me. Slaves still fear my rod; guards bow their heads and stretch out their hands at knee level before me. But bounds have been set to my walking, and no ships can put in through the surf of these shores; never again shall I smell the smell of black earth on a night in spring.

My name was once inscribed in Pharaoh’s golden book, and I dwelt at his right hand. My words outweighed those of the mighty in the land of Kem; nobles sent me gifts, and chains of gold were hung about, my neck. I possessed all that a man can desire, but like a man I desired more—therefore, I am what I am. I was driven from Thebes in the sixth year of the reign of Pharaoh Horemheb, to be beaten to death like a cur if I returned—to be crushed like a frog between the stones if I took one step beyond the area prescribed for my dwelling place. This is by command of the King, of Pharaoh who was once my friend.

But before I begin my book I will let my heart cry out in lamentation, for so an exile’s heart must cry when it is black with sorrow.

He who has once drunk of Nile water will forever yearn to be by the Nile again; his thirst cannot be quenched by the  waters of any other land.

waters of any other land.

I would exchange my cup for an earthenware mug if my feet might once more tread the soft dust in the land of Kem. I would give my linen clothes for the skins of a slave if once more I might hear the reeds of the river rustling in the spring wind.

Clear were the waters of my youth; sweet was my folly. Bitter is the wine of age, and not the choicest honeycomb can equal the coarse bread of my poverty. Turn, O you years—roll again, you vanished years—sail, Ammon, from west to east across the heavens and bring again my youth! Not one word of it will I alter, not my least action will I amend. O brittle pen, smooth papyrus, give me back my folly and my youth!

Senmut, whom I called my father, was physician to the poor of Thebes, and Kipa was his wife. They had no children, and they were old when I came to them. In their simplicity they said I was a gift from the gods, little guessing what evil the gift would bring them. Kipa named me Sinuhe after someone in a story, for she loved stories, and it seemed to her that I had come fleeing from danger like my namesake of the legend, who by chance overheard a frightful secret in Pharaoh’s tent and fled, to live for many adventurous years in foreign lands.

This was but a childish notion of hers; she hoped that I, too, would always run from danger and avoid misfortune. But the priests of Ammon hold that a name is an omen, and it may be that mine brought me peril and adventure and sent me into foreign lands. It made me a sharer in dreadful secrets—secrets of kings and their wives—secrets that may be the bearers of death. And at the last my name made me a fugitive and an exile.

Continue reading here…

1954 film made based on the book:

Posted in Other Topics, True History of Manwith comments disabled.